This interview was conducted by Andrew Reiner and Suriel Vazquez, and transcribed by Michael Leri. It was originally published on December 1, 2016.

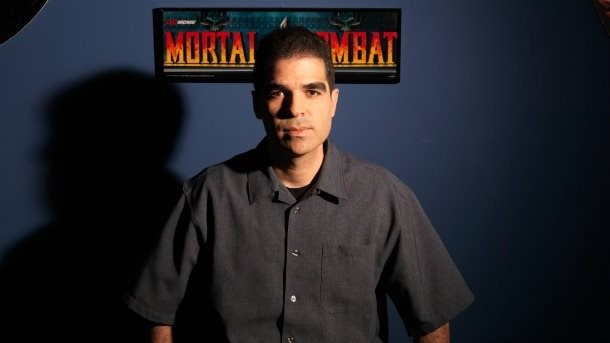

Ed Boon has likely been making video games longer than you’ve been alive. Years before he became the steward of the Mortal Kombat franchise, Boon was programming pinball and arcade games for companies that no longer exist. But despite his over 30-year history in the industry, he’s only ever really had one job.

To get a full view of what such a storied career looks like, we talked with Boon about his early days at Williams Electronics, some of the names Mortal Kombat could have had, and what it’s like working on the same series for over two decades.

Andrew Reiner: Let’s go all the way back, way back to first time you saw some kind of interactive entertainment like this. Take us through that day.

Ed Boon: I think my first interaction with any kind of interactive game, per se, would probably be pinball machines. From way, way back in the days of grade school. Our bowling alley had a bunch of pinball machines and we would play them. At the time, there was a concept called winning a free game. So you would get good at a game and the whole theory was “play on this for long a time with a quarter.”

Reiner: The bowling alley. Do you remember the name of that?

I know it was on Dempster Street. That’s the only thing I know. Because I remember it was down one main street from my house. I think it might have been called East of Eden’s Bowling Alley because there was an Eden’s Expressway. And it was just east of it.

Reiner: Do you know what took its place? Do you know if it’s there right now?

Yes. A furniture design store or something like that.

Reiner: That’s unfortunate.

There’s very few arcade-type things like that anymore.

Reiner: Where did you grow up and go to that pinball arcade?

I was born in Rogers Park, which is in Chicago, and we moved to Evanston/Skokie which is like a suburb of Chicago when I was in grade school. Like fourth grade or something. I basically lived there until I went away to college – and then got this job, as a matter of fact. I lived there for about the first two years of my job as a pinball programmer, I was saving up to buy a condo because I was on this big kick of “I’m never going to pay rent in my life.”

Reiner: And you went to school where?

For college, I went to [the] University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign. It’s probably about a two-hour, two-and-a-half hour drive from Chicago.

Reiner: So you’ve never lived anywhere outside of Illinois?

No. Never. But I’ve been outside of Illinois.

Reiner: Obviously, when we go to school we have a vision of a different future for ourselves. I was going to be an artist and draw Punisher comics. What were you envisioning as your potential career?

When I was in high school, there was the Atari 800, the Apple II, the Commodore 64, the VIC-20. All those kind of personal computers were becoming available. I do remember I did have an Atari 800 and I was programming in Basic, and then I started learning assembly language, and I started getting into that. That was like my hobby. Trying to figure out how graphics work and where to write in memory to get a pixel to show up on the screen. This thing called player-missile graphics and all these things.

So when I went to school I was like, “Well that will probably be my hobby all the time, but I’ll have a real job, a regular job to pay the bills.” That was kind of like my artistic output thing. But I lucked into this job through a little asterisk I put on my resume that got my foot in the door to be a pinball programmer, which kind of led me to being able to do video games. I never thought “I’m going to do video games” because I just for some reason didn’t think that was an option.

Suriel Vazquez: So when you made that transition from working on pinball machines to video game stuff, how much did you think your skills in designing pinball would transfer over to working on video games?

It was mainly programming. Ways of solving problems of writing software. For the longest time I called myself a programmer. I called myself the game’s programmer and the ideas for the game to me were like the easy part. The challenge was, “how do we make that happen? How do we make this spear come out of his hand? How do we make fire come out of his whatever?” You had a whole bunch of really good ideas, but the implementation part was [harder]. So you learn programming techniques and safe ways to program and quick ways to program. So I think those applied.

But the ideas were always like… you had more ideas than you had time to make them happen. So like I said before, the whole concept of a designer didn’t exist [until] many years later, even though I think I was deeply involved with design. I just kept calling myself a programmer. Those two jobs didn’t separate until many years down the line.

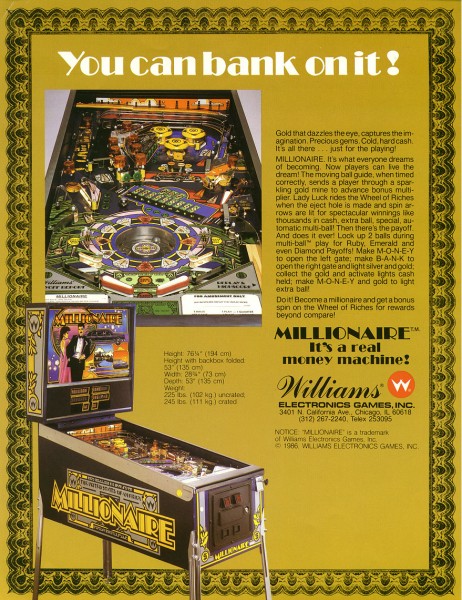

Reiner: When you went into your first day at work, your first game was Millionaire.

Yeah. They put me on a game called Millionaire, which was just being finished up and they said, “Oh, do lamp effects and display effects” which was like the closest you could get to video programming on a pinball machine. So I did that to kind of learn how the system works. How do you turn on a lamp? How do you make this flasher go off? How do you make the display show this animation? And kind of just getting used to it. Unfortunately, at the time I thought it was unfortunate, [but] apparently I did a pretty good job on it because they asked me to do it again for another machine and they asked me to do it again for another. And I wanted to have my own game [where] I would do the rules and the effects, the whole gambit of things that a game programmer does.

Reiner: Did you get to make your own table?

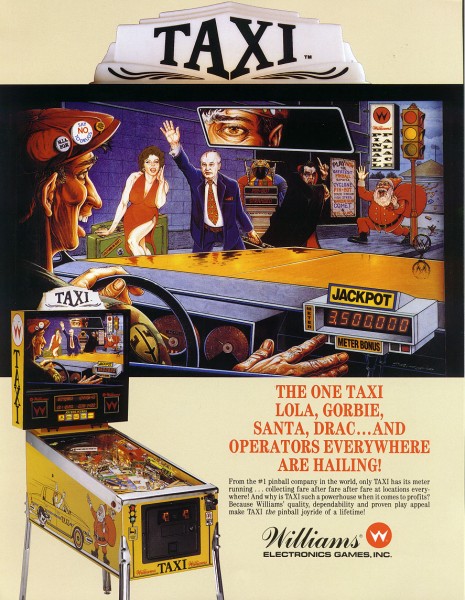

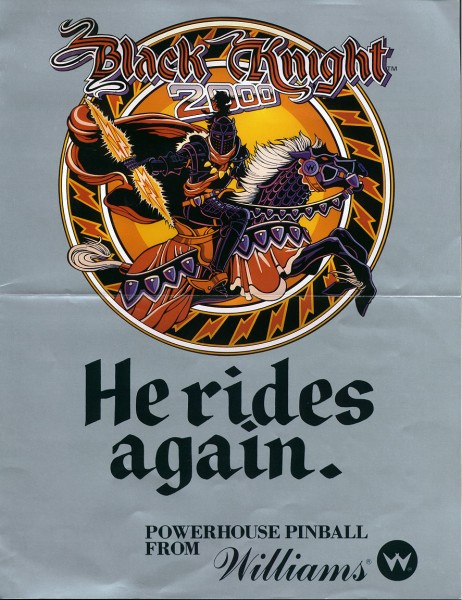

Well, I never designed the table but I eventually became a game programmer. I was the only programmer on the game. That was a game called Space Station, which was a sequel to a pinball machine called Space Shuttle. I did a game called Taxi, and finally I did a game called Black Knight 2000, which was a sequel to a huge, huge game in ‘80s. Black Knight 2000 was the last pinball machine that I had worked on before I moved downstairs to the video game guys who were working on NARC and Smash TV and all those kind of classic games of the ‘90s.

Reiner: Black Knight 2000, by the way, has the best soundtrack to date in a video game.

It does!

Suriel: That song is amazing! How did you guys go about making that dense of a song? Because it sounds very out of place in terms of putting it in a pinball machine.

That was totally the vision of a guy named Steve Ritchie. It was funny because he kept saying, “I want to hear a choir of angels singing.” It reminded me of how when people say what Freddy Mercury wanted for Bohemian Rhapsody was all the “Mama Mias” and stuff like that. And he kept pushing that. They went on the assembly line and they got these three or four ladies and they brought them into the studio to record these, “You got the power!” and all those lines that were in that game. And they sounded terrible. Oh my god. The two sound guys, Dan Forden and Brian Schmidt, who were the two audio guys in that game, they were just like, “This is not going to work. We have to get somebody who can actually sing.” I forgot who they found but they finally found somebody. But I remember that soundtrack to that game was certainly, especially for its time, was years ahead of its time. I still know the song in my head.

Suriel: Who does that voice… is that you?

The voice of the Black Knight?

Suriel: Yeah. The one who’s like “No way!”

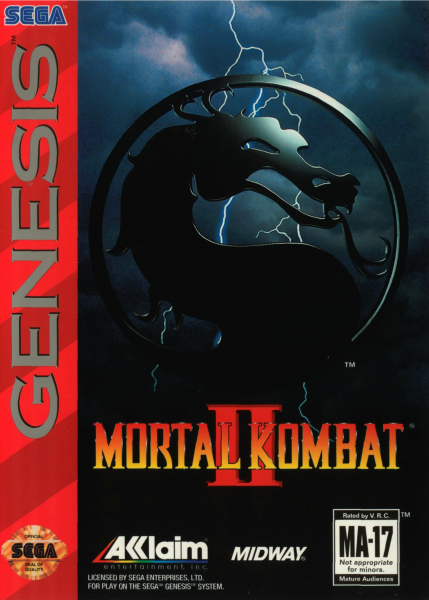

Yeah, like “Give me your money!” [Laughs]. No that’s the designer, Steve Ritchie. He had a really deep voice. He’s the same voice that was the Mortal Kombat announcer for Mortal Kombat 2, 3, and maybe 4? He was “FINISH HIM!” I was the announcer for Mortal Kombat 1 and then Steve Ritchie took over as the announcer for Mortal Kombat 2, 3, and 4.

Reiner: Can you recall the name of that first pinball game that you played? Do you remember the very first game you touched?

I don’t know the very first one. I know one of the first ones that I was like “Oh I like this machine” was a game called Evel Knievel. These were games that I think were even older, like were made way before I started getting into pinball. These were old machines at the time. I remember Evel Knievel, Bobby Hull Hockey. Eventually the more contemporary ones of like High Speed, Comet, and I think Pinbot. It was on the assembly line when I was interviewing with Williams Electronics.

I do remember when Space Invaders came. It was a new disruption, because everything was pinball machines and everything there was cranes or something like that, but all of a sudden Space Invaders comes and it’s a video game and this new tech and stuff like that. I remember my brother Mike really gravitated to it first. I was kind of stubbornly clinging on to pinball machines. Eventually I tried it and liked it, but I never really got like hooked on Space Invaders. It was more of a novelty to me. It wasn’t really until Defender came out. That was the first game I got really hooked and determined. Because it was so hard and so difficult to master, that’s when I really shifted my efforts towards video games.

After that, there was a string of games, each of which I became obsessed with for certain months. I remember Missile Command, Millipede, obviously the sequel to Defender was a game called Stargate and Robotron. It was huge chapter of my life, playing these games. While I was playing them, I just started noticing the name Williams above in the marquee where the title of the game was. And that was when I first started kind of realizing that somebody makes these games. I think when I was playing pinball I would see Bally/Midway and probably saw Williams at one point, but I remember Bally being the one that really stood out. But I just saw the word, “Williams” was on top. And Joust, Defender, Robotron, Stargate were the big ones that I had gotten hooked on.

So then go in high school and playing all those games and then into college…I had made one resume my entire life and it was for when I was a senior in college. I put a little asterisk on the bottom of it that it said for hobby or something: “Interest in video games and video graphics.” And it was very much like an afterthought. I know the Pasqual [programming language], I know Fortran, I know this and that. All these kind of more mundane points and then a little asterisk at the bottom saying: “Interested in video games.”

I guess a headhunter saw that and sent my resume to Williams Electronics, to the head of their pinball software at the time. I go in for an interview at Williams and I’m talking to the guy and I thought it was a job for programming video games because I honestly never… it never even occurred to me that somebody would write software for a video game. I think in my head, I was thinking of more of the electromechanical stuff with relays and all that where the logic was in the hardware. So the guy is talking to me and he says, “Pinball…” and I said “Pinball? What?” And he goes, “Yeah, this is for a pinball programmer.” I remember asking him, which was kind of dumb at the time, “Do people program pinball machines? People actually program them?” And he said, “Yeah this is what the position is for.” And so I was kind of like “Oh, okay, well that sounds cool.”

I think in my head I was thinking that it was still games. Like certainly in the category of a fun job as opposed to a regular job like everyone else has. So I said, “Yeah, okay, let’s talk about it.” So I’m talking to him and then they bring me to the next guy and then the next guy, I’m talking to him and he says, “Oh, what games of ours do you like?” And I say, “Oh I like Defender, Robotron, Joust” and then the guy says, “Oh yeah, I programmed Joust.” And I remember also saying to him, “Get outta here!” Like I literally thought he was joking with me! His name is Bill Pfutzenrueter and he programmed Joust, and he was now a pinball programmer and he was telling me about that game. And I was like, “Oh my god! I was hooked on that game!” I knew how to cheat it and all that stuff. I was kind of going on and on.

And then I’m talking about Defender and he goes, “Yeah down the hall is a guy named Eugene Jarvis, who did that game.” Then I started getting starstruck. Because I actually knew who Eugene Jarvis was. There was a video game magazine called Joystick at the time. This was way long ago. This was before the Joystiq website. I remember reading an article about Eugene Jarvis and Larry DeMar, and how they split off from Williams and did Robotron. From my perspective, they were the first rock stars. I remember a guy named Ed Logg who did Asteroids and Gauntlet. So these guys were like my heroes. Three of them worked in the company. That alone, I kind of felt like “Oh my god I’ve got to get this job.” So they hired me.

While the job has had a number of incarnations (I moved to the video department and then I did the home games), it’s really the only job [I’ve had]. It was Williams Electronics and then they split into Bally/Midway and then Midway Games and then Warner Bros. – it’s actually been the only job I’ve ever had. I’ve never quit or been fired.

Andrew Reiner: Get outta town! You didn’t have a paper route? You didn’t work at a grocery store? Anything like that?

Actually, that’s a good point. When I was 16, I worked at grocery store and I worked at a Cadillac dealer cleaning cars and stuff like that. But in terms of out of school, you’re done with school, this is your livelihood thing. It’s the only job I’ve had.

Suriel: That sounds wild to me.

Reiner: I had that exact same experience. I worked at a grocery store and then I worked at Game Informer and that’s it.

Yeah, it’s so weird when somebody mentions resumes and stuff like that. I’ve just had so little experience doing that.

I remember a pinball machine called High Speed, which was one of the more contemporary modern pinball machines that had music and voices and stuff, and I remember playing it and meeting the guys who had done that game. They had this long history of successful pinball machines: Black Knight, Flash. The programmer was a guy named Larry DeMar, and he was the same guy who did Robotron and stuff with Eugene Jarvis. He was now doing pinball machines and stuff. So I got to know them and to this day they’re good friends of mine.

My experience of learning about these games and philosophies of designing them and where to focus your effort and stuff came from Eugene Jarvis and Larry Demar, Steve Ritchie, Bill Pfutzenrueter. [They were] kind of like my idols. And I worked with them on and off for many years. Probably 10 or 15 years or something. Maybe not fifteen years. [They taught me] the foundation of how a game is made and what to focus on, especially Eugene Jarvis.

So I had worked on pinball machines, and I also started doing voice stuff because at the time there was no such thing as hiring an actor or professional. They were like, “Hey can you come in here and pretend like you’re a guy in the alley who’s being robbed?” and then you’d make up a voice or something like that. They started coming to me. And they kept coming to me. One designer, his name is Pat Lawlor, he did a bunch of big pinball games, he was doing this game called Funhouse. It had this puppet in it, Rudy. The whole time that you’re playing, he’s kind of taunting you and saying that stuff so they asked me to do the voice of that. It was like an entire script and everything.

So I was kind of doing that, programming pinball machines. And at the time Eugene Jarvis had come back to the company, and he started up a new hardware division and they started working on a game called NARC which came out at around 1990 or something like that. Maybe ‘88 or ’89 [’88 – Editor]. And so they had this really cool hardware and I just kind of kept going downstairs to look at what they were doing and saying, “Oh god this so cool.” I love doing pinball machines but the guys downstairs were doing video games and that was the cool place to hang out.

I talked them into getting a video system in my office, so I had pinball and video going on at the same time. I remember getting some of the graphics from NARC and making explosions and stuff like that. So Eugene and I, we had worked together on this pinball machine called F-14 Tomcat, so we were already good friends and he was like, “Yeah why don’t you come down and let’s start another video game project,” because they were done with NARC and they wanted to kind of start a bunch of things so a few games in parallel were starting to be worked on.

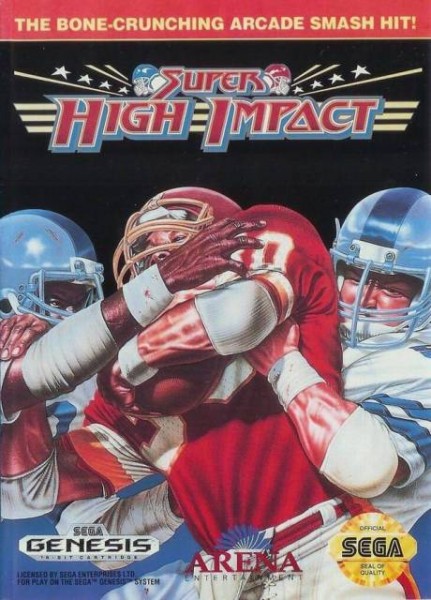

Mark Tremell came in to the company and him and John Tobias were working on Smash TV, which was this kind of Robotron-type of game, which was awesome. And then Eugene and I started working on a game called High Impact Football, which was a football game with digitized graphics and stuff like that. And again, we weren’t hiring professional hire actors… I was the football player. I put on shoulder pads and stuff like that and ran on treadmills.

Reiner: We’re going to call you the first Troy Baker. How about that?

[Laughs] Well, it was very much like a garage band production at the time.

Reiner: It sounds like it was just kind of like a friendly invitation, almost like how Valve is run right now, like “Hey come work on my project.”

It was much, much smaller in scale like teams were four, five, six guys doing a game together and the project would be nine months or they were a year long. Which is laughable now. It was very much off the top of your head, impromptu. There was no game design documents, there was nothing formal about it. “How could we do this? Well I guess we can try this.” Invention by necessity and all that. So this is the first video game I’m working on and it’s weird like manipulating images that are you. We were also working with artists on the game. It was a guy named John Newcomer. He also worked on the game Joust with that first guy who interviewed me.

So the game did really well. And Williams, that was kind of their thing like graphically, games like NARC and High Impact Football and Terminator 2, and eventually Mortal Kombat. What set the Williams games apart were the digitized graphics. And I remember Pitfall came up about the time we were doing that and we were so much higher resolution than they were. So we were starting to make a name for ourselves with the company. And the High Impact Football game did well so we did a sequel to that called Super High Impact Football. These were all arcade games. These were all games that you put the quarter in and all that stuff.

After Super High Impact Football, I wanted to do something new and without sequels so I worked on Mortal Kombat. [Laughs] During High Impact Football, I got to know a lot of guys in the studio and John Tobias was one of them and we were kind of hanging out, talking, and Street Fighter II had come out and the biggest thing was “Look how big the images are on the screen! Oh my god! Look at that!” Like this fighting game had very stylized graphics, like hand-drawn, borderline anime. And we said, “Let’s make the bad-boy version of this game. Let’s do something with blood. Kind of like the MTV version of Street Fighter.”

Reiner: So when you guys were getting Mortal Kombat started and you were doing your tests of the characters, were you digitizing yourselves in the game? Or did you bring in actors from day one?

In the very beginning, we wanted it to be a game starring Jean-Claude Van Damme and it was supposed to be… I think Bloodsport was a pretty recent release that he had. Bloodsport and Enter the Dragon and all these ensemble things where everybody kind of collects to fight in some kind of a tournament was the kind of theme that we knew we wanted to do that would allow us to have big variety of characters. So we took the movie Bloodsport and we played a videotape and digitized those images and put together like a demo using what we could find.

We made a demo and sent it over to Jean-Claude Van Damme. So we had put together this tape and this demo and kind of showed mocked-up graphics of what we would envision it to look like and then they contacted our guy who talks with the licenses and stuff and they said, “Sorry he’s already signed a deal with Sega” or somebody like that. Which was weird because we never saw that game. I’m still waiting for that game to come out 25 years later.

So we said, “Okay, well, let’s do our own characters.” John Tobias, at the time he was like, “Oh I know a bunch of martial artists that I went to high school with. Let’s bring some of them in and let’s shoot them.” It wasn’t even blue screen or green screen at the time. We just shot them in front of a wall and manually ripped away the edges frame by frame. And we did that super fast. We got a demo of the game running. God, it must have been… just a few weeks. Maybe in a month we got something running.

The big thing was this uppercut. Once we got this uppercut going and the screen shook and the guy flew up in the air then like suddenly everybody is coming into my office “Aw, let me see the game!” Our management all of a sudden… it was something that was real. It was something that people started talking about.

Since we do coin-operated games, we were also working in the building where they manufactured [the machines], so there was a factory and they had a production line and they were making pinball machines at the time. But they were trying to ramp up our offices in, I think it was by Gurnee, we had one that was building the video games and that showed, “Oh for this month we’re going to run out of whatever game we were producing at the time. Can you guys get this fighting game ready in time to fill that production schedule?” And we were like, “We can try” and we were much, much younger than we are now and so I had a lot more energy.

We put the game on test in an arcade like five months after we started it, after that first demo. With six characters. Sonya Blade didn’t exist. And there were four guys on the team: Myself, John Tobias, a guy named John Vogel, and Dan Forden who did music. And that was the entire team. Looking back now, it was odd just because…. I think in my head it’s just two guys on the screen. How hard can it be? Jumping around and stuff. So we put it on test and it was… I swear to god somewhere in my basement I have footage of that first test. But it was like the most surreal thing seeing 30, 40 people crowded around the game and when they would see something crazy happen when they just saw an uppercut or blood or something like that… they were literally running around out of excitement. Running around the machine.

So at the time we were like “Wow!” and we had tested games before and you really get an idea when you test a game how it’s going to do. And we had seen nothing like this. Our company got phone calls from distributors in Los Angeles. I remember one of our distributors [got] mad at us, saying, “What is this game that you’re testing that we’ve heard about?” People flew in from New York just because they heard this game was on test. Again, Street Fighter was huge, so arcades were just packed with people playing Street Fighter. And all of a sudden this new kind of bad boy-looking version of Street Fighter comes out and it was just taking over. It was ridiculous. So some people were flying in from New York and checking the game out, and then we pulled it after just a few days because we knew what the bugs were. So there were people who showed up and the game was gone and we started getting phone calls. It was like nothing you can really imagine, when you see something that’s on the cusp of becoming bigger than the team is.

And we got the game done in eight months. The game from beginning to end was eight months. Four guys. A lot of late night hours. There was no such thing as a designer. The position of designer didn’t exist. It was Programmer, Artist, Sound Guy. Those were the three positions on our team. When I think back to it, the design really was ideas. John Tobias, he designed the costumes and stuff like that. I designed what the guys did, what their special powers were and what their fighting mechanics were. It was a complete collaboration on our part, but as far as the actual work – the implementation of it, the programming in the moves – that was me. And doing the art and the animation and stuff that was John Tobias in the background. Graphics was John Vogel and Dan Forden was the sound. So it was a very tight four-person team. Very collaborative. That was kind of like what started this 25-year chapter of fighting games.

Reiner: What were you calling it back then? Obviously it was maybe Jean-Claude Van Damme’s Bloodsport. What were your initial names for it?

The first name before Van Damme passed… we wanted to call it Van Damme. We just wanted to see huge letters “Van Damme” when you walked by. You couldn’t pass that up. When that was gone, we threw so many names out there. Kumite was high on the list. Dragon Attack, which was a song by Queen. That was one that we were messing around with too. Death Blow and all these kind of… Death Blow, Final Fist or something… all these crazy, almost cliché martial art movie titles or something were a lot that we threw out. And then one time, we wrote the word “Combat” on the screen, on my grease board and changed it to a “K.”

Reiner: Why did you change it to a “K?”

Just to be different. Just to make it seem unique or something like that. The pinball designer that I had worked with on a few games, Steve Ritchie, he did a whole bunch of really successful pinball machines. He was just sitting in my office and we were talking and he’s like, “What’s that?” and I said, “Yeah we’re trying to come up with a name. It’s Kombat.” And he goes, “Why don’t you call it Mortal Kombat?” And I was like, “Oh my god, that’s it!”

Reiner: When you guys said you wanted to do that bad-boy version of Street Fighter or a fighting game, do you remember those initial talks of what that consisted of? Can you recall that original vision?

Yeah. Nobody was expecting anything out of us. We were just kind of working quietly, taking trips to costumes stores, trying to put together some kind of costume that might look cool with our video game digitized technology. It was great. Nobody was expecting anything so we just quietly did that.

And then all of sudden, there were expectations. Can we finish it quickly? Can we do this? And this was the first game that both myself and John were kind of heading ourselves. Because John did Smash TV with Mark Tremell, who was very experienced and seasoned game designer and programmer. And I did High Impact with Eugene Jarvis, who was clearly a legend. We had only each done just like one or two games. Actually, John did a game called Total Carnage which was kind of like Smash TV. And I was like voice of that guy, General Ahkboob. So we kind of knew each other from that and working together very, very peripherally. There was no expectation for it and that was very cool because we didn’t have pressure to finish something until the game started looking and playing fun. That’s when the pressure started.

Suriel: After the game came out, obviously sort of everyone knew what it was including people like Joe Lieberman, who started lobbying for stuff like the ESRB. Did you guys feel that pressure at all?

No. The timing of that is interesting, and a lot people don’t realize that we made our game and then it was a huge arcade hit. They sold tens of thousands of cabinets. In terms of the era of games that we were making, it almost tripled our other highest-selling game. It was ridiculous. Our company was just focused on producing as many of these as possible. I think at one time there might have been running the assembly line 24 hours or something.

Acclaim really smelled blood and to their credit, they identified Mortal Kombat as a potential real mass market [hit] outside of the arcade experience. I remember them telling us, “We’re gonna spend $10 million advertising this game.” I remember saying, “You guys better calm down. [Laughs] You’re betting too much! And I was totally wrong. When they brought it to the mass market and they made a TV commercial, that infamous kid screaming “MORTAL KOMBAT!” and stuff, when they did that and that’s when suddenly it hit the radar and that’s when it started getting attention for the violence. And the game had already been out for months, maybe a year. It was out for a long time. We were already working on the sequel.

At the time, there was no ratings system. And it was never an issue. It was kind of when hip-hop and all that stuff came out and all of a sudden there’s profanity in lyrics and stuff like that. And all of a sudden it was like, “Whoa, whoa, whoa. Records? We need to care what’s on them?” In the same way that you had to have “Explicit Lyrics” on a record, we all of a sudden needed [a label that said] “Hey there is violence in this game” and that, along with Doom and Night Trap and all that stuff, I think, just really made people aware that the ratings system was necessary. And we agreed with that. We never intended it to be seen by younger players.

Reiner: Did you ever think the game would have that much of an impact on people? That you’d have this really cool path into video games, and just being at the one company basically your whole life?

Yeah, I would never have guessed that… like I said, it was one job but in my head, it’s kind of like when you say, “Okay, I was at school.” There’s really… like there’s grade school, there’s middle school, there’s high school, there’s college. I had all these chapters of pinball programmer, video game programmer, programmer/designer, and then as Mortal Kombat, all the games. The first game was a team of four. The second game of a team of five. The third game was a team of seven. Then a team of nine. And it all of a sudden, Deadly Alliance was like a team of 25 and that was, at the time, “Oh my god this is crazy.” And then each game adds more and more people and we’re at like 180 people just like in our studio alone. And there are people in other studios who are working on the game too. Like this gigantic beast.

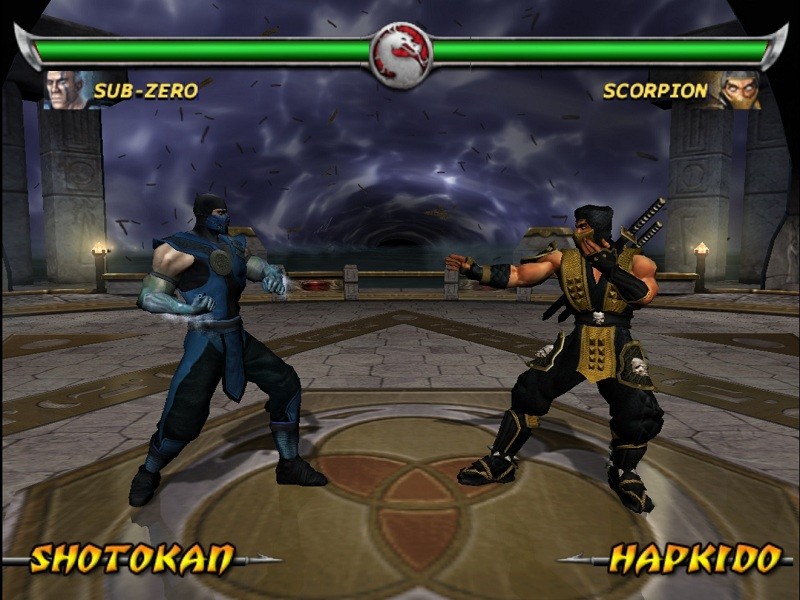

There was a big transition, also, between when Mortal Kombat 4 came out, and the writing on the wall for arcades was pretty clear. It was very clear that from a numbers standpoint, not only just the business end of it, but from like game players… Mortal Kombat 1, 2, and 3, one of the hooks of those games was the secrets.

We had a ton of hidden characters and the “Toasty!” guy popping out, just random things. I always wanted to see a question mark over the game. I didn’t want anyone ever thinking that they knew everything that’s in the game. A lot of folklore and lies and made up things come up surrounding the game, and I always loved that because it just kept people intrigued. The fact that the games did have secrets added a level of possible believability to it where people go, “Oh my god, maybe there is a secret ninja in the game? Maybe there is a secret character here?” And at around MK4, the Internet was becoming… well at least newsgroups and stuff like that were becoming… secrets were less discovered, and people were sharing things. And people didn’t have the same patience to learn things. And then home games were really taking over, as far as people spending more time on them.

By then the PlayStation was out. It was just a different beast, especially with the arcade market. That’s when we had made a huge decision. I remember everybody going, “God this is crazy to do Mortal Kombat: Deadly Alliance only as a home game.” That was the first game that came out that didn’t have an arcade game to work on and we were all nervous about it and then ironically it was one of our best-selling ones just because we were able to focus on stuff that was single player. We didn’t have to worry about designing the game so it would take a quarter from you every two and a half minutes or whatever that formula was. And the team was bigger.

[It also became less about] you picking your character and me picking my character. And then going at it. And then loop forever. That was when we started adding more content. And that’s, to me, kind of like where I talk about high school, college… that would probably be our like college years, where the game became more of a focus to home games. That’s when Tekken and Street Fighter kind of died down during those years. Tekken kind of emerged and I think Virtua Fighter had a bit of a presence there too, but Tekken was the big one that we were kind of going up against at the time. That was really when we transitioned out of coin-op into the home game and became a much bigger production. Bigger teams and bigger stuff like that.

Reiner: We kind of covered the big craze around Mortal Kombat and Mortal Kombat II. You talking about people going to the arcades and all that stuff. Maybe we can transition with Midway and maybe talk about Midway and then the unfortunate closing of that and kind of that next chapter in creating NetherRealm. Or if you think we are missing anything in Mortal Kombat 4 or Deadly Alliance, that era.

Those two are kind of related to each other. Acclaim had exclusive rights to all of Midway’s games for a certain period of years. So they had Mortal Kombat 1, NBA Jam, Mortal Kombat II, and then NBA Jam Tournament Edition. Those were like four back-to-back games that were multimillion-selling games that were all under the Acclaim deal. I know that that’s when Midway management decided they were going get into publishing home games. Because we were strictly about coin-operated arcade games, and then Acclaim was handling the home conversions and the advertising for it.

So Mortal Kombat 3 was Midway. I think they bought a company called Trade West that was in San Diego, and that was kind of like us getting our foot in the door for that stuff. And so there was a lot of hype with MK3 because we were publishing it ourselves. So that was really big. A few years afterwards, arcades started to kind of slide a bit. And we were working on Mortal Kombat 4, which was in 3D. Mortal Kombat 4 came out and we published that, and it didn’t do as well as MK1, 2, and 3 did in the arcades. The arcade market was really nosediving really fast.

So we published the home version of Mortal Kombat 4 and then I remember us kind of raising the question of, “Should we just go directly go into the home for the next Mortal Kombat game?” And we spoke to our arcade distributors and for years had already been saying how much the market had gone down and how expensive these games were and our hardware was getting more expensive. So after talking with them we made the kind of the difficult decision to skip arcades and go directly into the home. And that’s what Mortal Kombat: Deadly Alliance was.

And there was kind of like a trilogy of those games, in the 3D days. Tekken was coming out and making a big impact. There were some other 3D games, Virtua Fighter, Dead or Alive. Not quite as big as Tekken was, but Mortal Kombat kind of went into 3D, even Street Fighter went into 3D. They had the Street Fighter EX games and that was like the thing for fighting games was 3D and all that.

And Deadly Alliance was a huge. It sold way more than Mortal Kombat 4 did. We had a bunch of features that were specifically for home versions. The formula for doing an arcade game is a completely different animal. 2002 I believe was Deadly Alliance, and then 2004 was Deception and 2006 was Armageddon and in between then we did and action-adventure game called Shaolin Monks which was between, I think, Deception and Armageddon or one of the two.

So there was a period of time where we were really cranking out the games. Like in my opinion, a little bit too frequently. Even though Shaolin Monks, the action-adventure game, was a different type of game, it was still Mortal Kombat again and was like a year after the last fighting game and whatnot. So that was a very busy time.

I distinctly remember going to you guys at Game Informer, and we brought up, I think it was Armageddon, and we were showing you all the stuff and you’re like, “Oh my god! How many characters?” And then we showed you the kart game and I look over and Ryan was all like, “What the hell?” It was a funny moment of, “What else are you guys going to cram into this game?” I would always call these games diversions. Because we had done a puzzle game, Puzzle Kombat. We had our full fighting game but there was just another menu selection thing that was Puzzle Kombat and then we had done the Motor Kombat one and the volume of content was really getting out of control.

Reiner: How did those things come to be? Was that like game jams you did in the studio? Or did you just go “Let’s do a kart racer?”

I think to some extent it was kind of scratching an itch that we had of working on a different type of game. The benefit of the games doing well was that we stayed in business. There was always the negative, I don’t know if you call it the negative, but the challenge of it was there was always the hunger for another one. So the idea of not doing a Mortal Kombat game was a difficult sell, especially with Midway having their financial challenges, they really relied a lot on having a dependable game. So a lot of that “Oh god we all love Mario Kart, we all love Tetris, and all the puzzle games coming out.” So we thought it would be like a cute thing. And Street Fighter had that puzzle game too. And so it was us scratching that itch. But after Armageddon, it had like 50-something characters and had Motor Kombat. I certainly felt like it had just reached a point of “Okay, we’re not going to do 70 characters next. We’re not going to grow anymore.” We had kind of really done that as far as I was concerned.

So the whole idea, one of our marketing guys, and again this was the tail-end of Midway, one of marketing heads developed a relationship with DC Comics and we were talking about doing a DC fighting game and then he suggested, “Hey, what about a Mortal Kombat versus game?”

The challenge was, well, obviously we’re not going to cut Batman’s head off. We’re not going to cut Superman’s head off. But it’s a Mortal Kombat game. Do you make it a M-rated game or do you make it a T-rated game? And we had decided to make it a T-rated game. People who loved Mortal Kombat for what Mortal Kombat was didn’t get to see all these creative, gory crazy fatalities. There was a cool novelty of, “Oh wow! I see Batman and Sub-Zero on the same screen and they’re fighting each other.” It was a fun “what if?”

So the game sold well but it absolutely created this hunger for a tried-and-true, no-holes-barred Mortal Kombat game. And that really set the stage for Mortal Kombat 9. We finished up Mortal Kombat vs. DC literally in the midst of Midway going under, and so we were working on our game and people were leaving. Our building was getting more and more empty. I remember at one point we had a Mortal Kombat team, an NFL Blitz team, Red Card Soccer, and all of the Hangtime, and Showtime, and the basketball games with NBA and even Psi-Ops and Stranglehold and all that stuff. And over the course of a year or so that became smaller and smaller and smaller until it was just us.

Reiner: So your whole dev team was intact through Midway closing?

Yes. We never laid off a person from our team ever since it was the first four guys. And that was important to us. As you’re facing financial challenges, the subject is going come up of, “Well, can you guys trim back this? Can you make cuts here?” and with everything that was going on there was an understandable nervousness amongst some of the guys on the team and I personally was insisting on principle, we’re not going to let anybody go because this team has been producing and has been doing that. That was a real sticking point. And they were totally understanding.

So Warner Bros. came. Actually a number of other companies were kind of in the running. I remember speaking with a number of companies. But Warner Bros. came and it was clearly the choice. At the time, the first thing they said when we were finishing up Mortal Kombat vs. DC and working on MK9, was “We want to give you six more months to do this game. We really want to make it as good as it can be.” Which was very different from our normal “Hey it’s been two years. Where’s the next game?” kind of thing.

So Mortal Kombat 9 was this huge return. It was a return because we had just done a T-rated game. It was a return because we were going back to 2D gameplay. The whole 3D games of Tekken, Virtua Fighter, and Dead or Alive and stuff weren’t as strong as they once were. They felt like they had peaked. So we were like “Now is the time to really hit.” We decided to bring back all the nostalgic characters [from Mortal Kombats] 1, 2, 3. And that was like this crazy grand slam. That was actually the highest-selling of all the Mortal Kombat games almost 20 years later, which was crazy. Usually the first few of a versions of a game are the highest-selling ones. So that was crazy and Warner Bros. really backed us.

Reiner: On that note, when I talk to developers that kind of reset like you guys kind of did, they always say that’s like the last option they really think about. Were there some other directions you were thinking maybe considering taking that before you kind of settled ongoing back to 2D and all that?

No. To me, I used to use the term “The planets were aligned.” It was a perfect setup. Perfect storm of MK vs. DC being such a departure as far as the different characters and the T-rated game, and so much of the feedback was “Okay that was fun but you’re doing a true Mortal Kombat game next, right?” That was the definitive message we heard from players and so it wasn’t even a choice. I used to, in pitches and stuff for this game, I said the story of this game is just the story of going back to 2D, M-rated game, returning characters, retelling the MK1, 2, 3 story. I don’t think that setup would ever happen again in terms of the hunger for it.

Once we got the word out of that’s what we were doing, it became really crazy. MK vs. DC had introduced that whole cinematic presentation of our story mode, where you go in and out of the fights, and we really felt like we could perfect that with Mortal Kombat 9. So again, that was another big home run for a big feature that everybody loved. And that was the first Warner Bros. game, Mortal Kombat 9. MK vs. DC was the last Midway one. We did MK vs. DC with the building just slowly being less and less occupied every week. It was weird.

Suriel: So with Mortal Kombat 9, something that you guys also seemed to focus on was having some of the guest characters. How did that stuff come about?

In addition to that, the guest characters, it was also the first game that we did do downloadable characters. [For] MK vs. DC, we actually did have Quan Chi and Harley Quinn that we partially developed to add as DLC characters. But again, because of the complexities of switching over from Midway to Warner Brothers and all of that stuff and the timing of a number of things, we just never released it.

So we knew we were going to do DLC characters for Mortal Kombat, and since Warner Bros. is a huge entertainment company and you have access to a number of different… they’re very collaborative. Like TV and movies and video games. Stuff like that. So that just kind of gave us access to some of these characters through whatever business deals they did. Then it was again, scratching a little bit of that itch of “Oh wow! Freddy Krueger is on the screen with Scorpion. How cool is that?” We draw a lot of inspirations from some of the horror movies and the Nightmare on Elm Street games. The Nightmare on Elm Street movies come up in a lot of our meetings for fatalities. “Oh remember in that movie when they did that?”

Reiner: Take me through really quick. Are you just sending an email to someone at Warner? Like “Hey can we add Freddy Krueger to the game?” And then does it go to legal? What is that like?

It was more like, “We’d love to do a guest character, who’s available?” And then we would see a list of 10, 15 characters. We didn’t want to do another DC character because we were an M-rated game. I remember they brought up Neo. So there were a whole bunch of ones that for business reasons or that creatively we didn’t think they’d fit. After further discussion, we kind of realized that the horror characters tend to lend themselves to it. Jason, Freddy, Leatherface. So a number of those characters had come up in our discussions with Mortal Kombat 9, but for whatever reason we chose to do Freddy.

Suriel: After 9, which was, like you said, a return to form and sort of going back to 2D and sort of resetting a lot of the plotlines. So what prompted the change in direction for Mortal Kombat X where you guys sort of went from completely classic to this sort of new direction with replacing a lot of the older characters with a lot of new ones. I feel like X feels like the game that has had the most new characters since 4.

It was a conscious decision. You’re right. I think it was the most new characters that we’ve added almost ever. It was the exact opposite of Mortal Kombat 9 strategy-wise, because we felt like MK9 was like this homage to the first three games. We literally told the story of the first three over again with our cooler, more cinematic presentation. We didn’t introduce new characters. It was Kabal, Stryker, Raiden, and everybody all coming back and it scratched the itch of nostalgia.

After that, we felt it was time to do the opposite. It was like “Now this game, MKX, is all about new.” It’s all about a bunch of new characters. We’re obviously going to have Scorpion, Sub-Zero, the staple characters, but let’s really introduce a lot of new elements to it and that was the character variation system, Brutalities, and all these new characters and a brand new storyline and everything. So we really felt like it was time to kind of like, just like Mortal Kombat 9, it was time for a return to the roots. Mortal Kombat X was time for newness. New novelty. New features. New everything.

Suriel: One of the other recent things that’s happened with both Injustice and Mortal Kombat was the rise of the competitive scene for those games where before 9, there was sort of some high-level play but it wasn’t sort of prominent within those communities. But since 9, it seems like that scene has picked up more and more steam in recent years. Was that something that you guys looked at when you were making 9 or was that something that snuck up on you?

When we were making 9, EVO had obviously been a huge thing for many years. People suddenly were playing a lot more online, fighting games online and then it became you had more and more people to play. We saw this kind of resurgence of things and Twitch came along and people streaming their games, and it was such a fact that we went back to our 2D gameplay. I think we had a significantly better fighting engine in Mortal Kombat 9 than we did in MKDC or Armageddon or something like that.

So that suddenly pulled a lot of players who were playing it really seriously. And then on top of that, eSports in general was just getting traction and taking off. Certainly when we made MK9, it was like “Oh that would be cool” but when we made MKX it was like, “Hey this is something that is out there. This is something that we need to support and accommodate and put features in our game that will make it easier.” It’s part of the recipe of making a fighting game is supporting eSports right now.

Reiner: Take us back to those discussions on getting Injustice off the floor. Take us through the creation of those first days of Injustice.

When we joined Warner Bros., DC was a part of Warner Bros., so that was a nice kind of coincidence. And DC was going under some changes and whatnot too, so it was different people that we were dealing with. So DC was happy with MK vs. DC and we saw two opportunities with MK vs. DC. One was Mortal Kombat going back to its roots and another game that just celebrates the super hero experience. And that’s what Injustice was.

We actually knew we were going to do Injustice while we were working on Mortal Kombat 9 because to me, it was such an obvious next step to do. You do Mortal Kombat vs. DC and then you go “Okay, let’s do a pure Mortal Kombat game and let’s do a pure super hero, battle-of-the-gods fighting game.” And that’s when we introduced the bigger scope of fighting where you have multiple arenas and the big transitions and the super moves and all that stuff. So it was really just kind of like a 10 out of 10 Mortal Kombat experience in terms of it’s purely Mortal Kombat and then follow that up with a pure super hero experience. In our eyes, we were just like “Yeah this is obviously the next thing we should do after Mortal Kombat 9.”

Reiner: Obviously comic book companies have their own set of rules with their characters, they’re very protective of them. What kind of exchanges of ideas was there in creating this stuff? Because you guys are known for uber-violence, smashing characters through walls. All that kind of stuff. What kind of leeway did they give you in making a super hero game for them?

Injustice was kind of like our first interaction with the Geoff Johns era and the guys at DC who worked around him. He was just becoming the Chief Creative Officer I believe. I don’t know what the exact timing was but he was the guy who we were basically talking with. He was surprisingly open to new ideas. So we’re doing all these things. We’re slamming cars on people and doing all this stuff and he was really like “As long as you’re staying true to these characters.” There wasn’t as “Well this boot should be a little bit higher on his calf.” There was none of that. It was just as long as we’re representing these characters and the kind of spirit it is. That was the main criteria. I have a ton of respect for him. It was a very different experience than doing Mortal Kombat vs. DC.

Reiner: One of the strange outcomes of this game was the lore took off. Your story continues in comic books up to this day. They’re just starting to transition again. Did you ever foresee a story in a fighting game especially something like this having that kind of staying power?

No. We were excited about the idea that the foundation that we were kind of setting of “Hey this is an alternate universe and in this universe Superman has gone crazy. He’s gone rogue and become this tyrant.” And this was part of what this boundary that we were allowed to push. And because DC has this convenient multiverse thing where you say “Hey this isn’t the same Superman that you know.” You have all these decades of history that you need to be consistent with. We said, “No. Our Superman is this. Our Batman is this.” That just gave us so much more elbow room and creative freedom to do things that are out of the ordinary for these characters. Superman killed Joker. What the hell?

I think some other people identified with that creativeness, and one of the guys was the writer, Tom Taylor, who was writing the comic book, he just went crazy with the idea. Because there is this big gap in our story that we kind of fast-forward through, [and] we were like, “Hey Tom, can you fill in those gaps?” He just completely embraced it. The comic book and the mobile game, which was another surprise thing. They were the two kids who graduated. You raise your kids, they graduated, they left and they were successful on their own. It was such a cool thing to see happen, the comic book having its own life independent of the game. The mobile game was this surprise, lightning striking, out of the blue that just became this monster mobile game. And all of a sudden, there’s these three independent really strong representations of this Injustice universe that have been going strong ever since. That, to me, is one of the coolest things about that whole experience.

Reiner: Obviously after the first Injustice, after the success of it, lightning struck twice for you guys. The sequel was a no-brainer. You guys haven’t talked too much about the narrative of Injustice 2 yet. Can you go into that a little bit, of building off the lore from the first game?

Well we actually do have a big campaign. We’re going to drop a really cool piece of content. Then we’re going to unravel the story of that. So I can’t really get into a lot of the details of it now. What can I say that doesn’t ruin it? It certainly continues with the story and, as you can tell from the roster, there’s a lot more characters that are introduced. I’ve already said this at Comic-Con, that Supergirl plays a very pivotal role moving forward. I feeling like I’m holding back so much.

Reiner: [Laughs] I understand. But it will be continuing what is there to a degree.

Oh yeah. And the story that we have is, the presentation, is more elaborate as far as the story and options and stuff like that as far as what could happen. It’s not as black and white as the first one.

Reiner: Here you are working on Injustice 2 coming out next year, 30 years since you started in the industry, when you look back on it, what’s the first thing you think?

Looking back, it doesn’t feel like 30 years. I went to a thing called Pinball Expo this last weekend. They do it every October in Chicago and I always go to it and I always meet up with friends that I was working on games with when I was doing pinball machines and everybody is always saying, “Oh my god, look how young we look here! Look at how old we are now!” The thing that keeps popping into my head is it does not feel like 30 years. It doesn’t feel like that amount of time has passed. I guess it’s odd but as far as Mortal Kombat is concerned, 25 years, oddly MKX is going to outsell Mortal Kombat 9, which is even crazier. I feel fortunate just to have been part of that whole wave. The highs and lows and everything. Just like to be at this point now where we are is just amazing. It does not feel like 30 years.

Reiner: I can’t think of another game developer who has been on a series as long as you have for Mortal Kombat. What is it about this series that has the staying power for you as a creative talent? Like what do find about this that every day you get up and go in and are excited to make a new game? What’s the allure there?

I’ve always been of the opinion that if we don’t change something dramatically with each iteration, that’s when people start feeling like they’ve already played the game. As a huge fan of other fighting games, I’ve seen other fighting game series kind of dwindle down a bit just because they just put prettier graphics on an existing engine that has been around for 10, 15 years or something. That’ll work for a while but after a while but people are just like, “Yeah, I can rent this one.” As long as we’re doing something new and adding something dramatically different, it’s still cool to me. At the same time, it’s always fun to do new stuff like Injustice and Injustice 2 where we’re able to kind of explore a different type of fighting mechanic and different types of characters, presentation, etc.

Reiner: So 30 years later, you wake up in the morning, you still love going to work, you’re still itching to make new games, all that stuff?

Yeah. I don’t have the same energy that I used to back in the day, when I was the only programmer. All-nighters were… that’s how you caught up. “Oh, we’re behind on this!” “Oh okay, I’ll just stay here.”

Reiner: What was your energy drink of choice?

I never got into the Red Bulls or anything like that. I was purely a caffeine person. Just a stream of Diet Cokes.

Reiner: As your endgame, I see two options for you: When you’re done 30 years, 40 years from now, when you retire, you either have to somehow get the Bloodsport version of Van Damme into a Mortal Kombat or you have to go back and make a Mortal Kombat pinball machine by yourself in your garage.

[Laughs].

Reiner: Those are the only two options I see.

Those are great full-circle stories. I’ll have to think about that.

Reiner: Awesome. Well I think that’s it. Ed, you do look the same age from when I first met you. Just your hair is shorter.

[Laughs].

Source: Game Informer The Definitive, XL Interview With Mortal Kombat's Ed Boon