Tunic started with a difficult choice for lead developer Andrew Shouldice: stay at his stable job or take the plunge and quit to work full-time on his budding game idea. In 2015, Shouldice closed his eyes and jumped. However, when asked why he made that decision, he initially hesitates.

“Why indeed?” Shouldice answers after a beat with a chuckle and a dramatic tone that suggests Tunic’s development cycle was a long one. There is no single incident he can point to that spurred him into making his choice. Instead, several factors, including how much he enjoyed making past one-off projects and his dwindling excitement for his job, influenced his decision to strike out on his own. His departure wasn’t without uncertainty.

“I remember thinking to myself; this might be a bad decision,” Shouldice says. “But I would rather make the bad decision now than always wonder what could have been, you know? Which is very cheesy, I understand. But that was sort of the thing that ended up pushing me over the edge. I really want to do this. Maybe it’s a bad idea, but I have to know.”

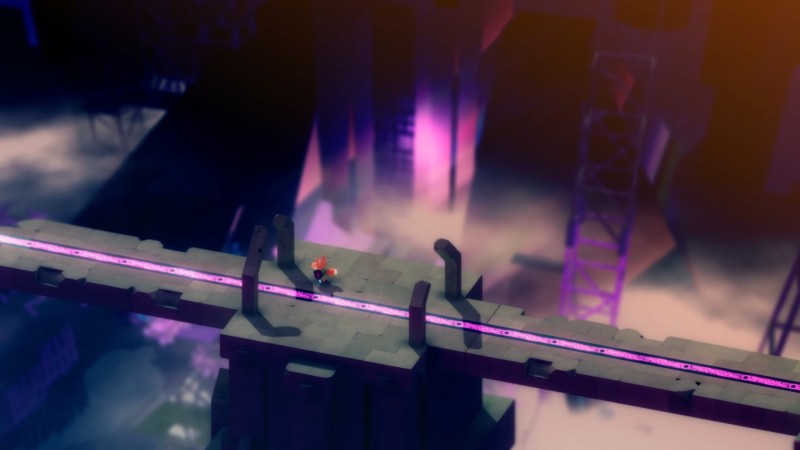

Seven years after its inception and four since its grand debut on the E3 stage, Tunic has finally launched. The vibrant isometric action game puts you in the boots of a sword-wielding fox fighting through a world of winding paths, mysterious structures, merciless enemies, and hidden secrets. Its art style, combat, and setting earned Tunic an ever-growing crowd of fans over the years. But while it’s currently one of the highest-rated releases of the year, Tunic started as a small solo project.

The Adventure Begins

Free of his employment safety net, Shouldice sat down – coffee in hand – to work on a project that wasn’t even a fully formed concept. His only direction at this early point was to make a game “with lots of secrets” and a protagonist “going on an adventure.”

That moment was when the game’s now-familiar vulpine hero started to take shape. Despite the sword-wielding fox being one of Tunic’s most endearing elements, it exemplifies the project’s early uncertainty. The creator admits the idea for the creature stemmed, in part, from his limitations in modeling humans. And this wasn’t an outlier. Shouldice recalls he struggled a lot with inexperience in the early development process.

“This is the first large-scale, commercial 3D game that I’ve made,” says Shouldice. “And for a long time, I was the only person putting code into it. And I was a programmer by trade, but there are a lot of things to learn about video games. And the programming part wasn’t necessarily the trickiest sphere.”

Realizing he would need some support, Shouldice began to look for additional creators to help him craft his game.

Shouldice first sent an email to Terence Lee, who, along with his wife Janice Kwan, would later work on Tunic’s soundtrack. Though excited by the idea of the project, Lee was unsure if he’d be available to compose for the adventurous title due to other obligations. Later that year at 2015’s Game Developers Conference, Tunic’s lead developer managed to connect with Lee and Power Up Audio’s Kevin Regamey, who would go on to lead the design of Tunic’s sounds.

Regamey recognized Tunic’s potential after playing a very early version of the game. “I played this build for, like, 10 hours,” says Regamey. “It was crazy. [Power Up Audio] all played it as a team, and we’re like, ‘Who the hell is this guy?’” The moment was even more remarkable for Regamey when he remembers Shouldice saying, “‘This probably won’t make it in the final game.’ And it’s true [that] nothing in that build’s in the final game.”

Luckily, not everything from the game’s humble beginnings was scrapped, including the concept for its surprisingly tranquil music. “I always liked that contrast in the game of it being really visually and aesthetically gentle and pleasing but also being difficult gameplay-wise,” says Lee. “So, when I made music for it, I intentionally tried to make it a bit more chill and relaxing. And I think a lot of people connected with that.” Both composer and audio designer emphasize how vital the soundscape is for Tunic, with Regamey saying, “The audio is almost like a character in that world… there are a lot of moments throughout the game where it is necessary and important for the audio to take the spotlight. The music and the sound are kind of one-to-one with all these other things, like the game design and the level design and the art.”

Stitching Tunic Together

With new teammates onboard helping to create a concrete and executable game, the early notions of secrets and adventure started getting fleshed out. One concept that enthused Shouldice was “visually pleasing and beautiful” isn’t inherently “on the opposite end of the spectrum of difficulty.”

“I think there are places for games, like some early Zelda games,” says Shouldice, referencing a prominent inspiration for Tunic, “[that] are beautiful and colorful, but still have that amount of difficulty and challenge that encourages you to be brave and to go to places that maybe you’re not ready for.”

Here, Shouldice’s idea of a game with adventure becomes apparent. He sought not only to create an experience where the character goes out into the world to fight foes and open treasure chests, but one that encourages the players themselves to be adventurous.

“One of the most exciting moments for me when playing a game,” says Shouldice, “is seeing something scary and having that thrill of ‘I need to run away, or I need to deal with this.’” This idea is not just limited to combat. Tunic’s developer suggests that stumbling on seemingly impossible challenges or treading on ground that feels off-limits while exploring is a vital part of the games he admires. In Tunic, Shouldice says he wants players to experience the rush of thinking, “Maybe you’re in a place where you’re not supposed to be right now, you know? Maybe you’re really exploring in uncharted waters now.”

Nostalgia was also instrumental in shaping Tunic. It’s clear the game takes many visual and design cues from NES, SNES, and Game Boy-era Zelda entries, but there’s more to it than that. The team talks about trying to recreate the feeling of finding unexpected lore in a game’s instruction booklet or putting your head together with friends to figure out the answer to a challenging puzzle – something that has become less common when players can simply look up a guide online. One of the easiest places to see Tunic’s retro design aspirations is in the in-game illustrated guides scattered throughout the world.

“The pages that you pick up are more than just a collectible. It’s not just you know, ‘I got all the manual pages. Hurray for me,’” explains Shouldice. “But maybe you’ve had this experience of flipping through a manual for some game and having that be an extension of the game experience itself. So, it’s not just, ‘Yeah, I know how to wall kick.’ The game tells you all about that. Sometimes there are secrets; there are things that you can only find out from reading the manual in those old games, and Tunic is definitely that way. There are plenty of things that you will have to pore through these pages to figure out.”

Last Puzzle Pieces

With the core game coming together, producer Felix Kramer joined the crew and, in 2017, publisher Finji – which previously worked on Chicory: A Colorful Tale and Night in the Woods – started working on ways to spotlight the project. A year later, Tunic took center stage at Xbox’s E3 showcase.

“Having the trailer appear there was a treasured memory for me,” says Shouldice. “I don’t know if it’s a warm, fuzzy memory because I lost a lot of heartbeats that day. But that will definitely stick with me.”

While the team had been working on Tunic for three years, 2018 was the first time many people became aware of the game and began watching its development. That group of new fans included various game makers, who connected with the project and, consequently, began incorporating some of its ideas into their work. “Every now and again, people will say that they’re drawing inspiration from [Tunic],” says Shouldice. “And given that this game so deeply draws its inspiration from other things, it’s pretty special to hear that other people can see it and, you know, feel that same feeling and want to make stuff themselves.”

One of those people was Eric Billingsley, who began working on Tunic as a level designer in 2020. “Previous to that, I was working on my own solo thing, Spring Falls, and Tunic was one of the visual references I was using. So, it was exciting to come on to [Tunic],” says Billingsley. “At that point, the game was pretty much solidified in most of the areas, but a lot of the areas still didn’t look final yet. So, my job was to go in and bring those areas – make them look nice, like the stuff that had already been seen in the game.”

The Developing Difficulties

Having admired the game from the sidelines, Tunic’s newest member may have been excited to get started, but he was also realistic. The level designer was stepping into the middle of an ongoing and years-long development process. Thinking back over that time now, Billingsley recalls not only his continuing enthusiasm but also the obstacles he faced in his new role.

“One of the biggest challenges I found is, because the game is so stylized, sometimes it’s hard to tell when things look finished or not,” says Billingsley. “If you go too detailed, it doesn’t look like Tunic anymore, and if it’s not detailed enough, it doesn’t look like a finished thing. And keeping track of how everything is connected is even sometimes a challenge when it comes to level design.”

But many problematic aspects of Tunic’s design also feed the game’s strengths. Tunic’s isometric perspective, for example, initially felt limiting to several team members. Billingsley acknowledges the view could be restrictive, but “the hidden benefit of that is now it’s very easy to hide little secret paths.” Conveniently, this plays right into Shouldice’s vision of a game stuffed with secrets that prompt engaged exploration.

Power Up Audio’s Kevin Regamey also weighed in on the isometric perspective, saying it could “result in you hearing things that you can’t even see because [the sound’s source is] beneath the pane of the camera view.” But, mirroring level design, this constraint turned out to be a blessing in disguise. “As it stands now, there’s basically no 3D audio in the game, in the traditional sense,” says Regamey. “Everything’s playing back in 2D; it’s just like playing sounds. And it feels a little more one-to-one with how things were done back in the day.” Again, that unexpected result reinforces Tunic’s direction, this time emphasizing its old-school sensibilities.

How Time Flies

The fully assembled team worked furiously on Tunic over the past few years to prepare it for its 2022 launch. During that time, Tunic’s lead developer was aware that some fans had been waiting half a decade or more to get their hands on the game and blames himself for the long wait.

“I’m the person that’s responsible for the development time, I think,” says Shouldice. “There was content creation and level design and learning how to make good animations and all those sorts of things. I think it’s probably safe to say – maybe the others could correct me – there’s no part of this game that has not been revised at least once or twice. I think the model of the key that you get early in the game might be the first version of itself. But a lot of other things are second-generation assets that have been rebuilt as I’ve learned more about what this game is.”

Eagerly admitting the process took longer than any of them expected, his teammates underline other reasons for the extended development. Composer Terence Lee muses on how, in the beginning, no one really knew what the final project would even look like, resulting in ever-shifting work. Additionally, the game’s audio and level designers emphasize some time-consuming, but necessary changes demanded a sizable chunk of the developers’ time.

“It’s a small, small team,” asserts Billingsley. “There was no way to do this project very, very quickly.” Especially since, according to Billingsley, the original size of the game was “twice as big, but it was mostly empty space.” Regamey, though hesitant to talk about cut parts of the game for fear of disappointing fans, did go on to reveal one section of Tunic that eventually got the ax.

“There once was a desert in Tunic,” Regamey explains. “There is no longer a desert because running across dunes was decidedly not as interesting as the other parts of the game.”

The Final Stretch

The team finally saw the finish line after revealing Tunic’s March 16 release date at The Game Awards in December. The announcement was a big achievement for the Tunic crew, as their trailer opened the massive show – which scored a record-breaking 85 million livestream views that year. When the finish line was in sight, it was hard for many of Tunic’s creators to decide whether they were relieved or nervous that the journey was almost over.

Looking over the experience, Shouldice shares his wish that Tunic “managed to capture that sort of childlike wonder” the games in his youth inspired. “And whether or not people get that feeling from the finished game, I don’t know,” says Shouldice. “I hope so.”

Source: Game Informer Tracing Threads: The Making Of Tunic