Like clockwork, MLB The Show’s arrival each spring always brings a familiar face. Ramone Russell has been there front and center to tell us what is new in each edition of this annualized series. Ramone is Sony Interactive Entertainment’s product development communications and brand strategist, but I’ve always jokingly called him “the face of The Show.”

In the years I’ve interviewed Ramone about The Show, I’ve learned he has an inspiring story to tell. People always ask me “How do I get into the video game industry?” and there’s no easy answer to that. Everyone’s journey will be different, but it always requires patience and a drive to make it. That drive is the backbone of Ramone’s story. He knew he wanted to get into video games and sacrificed everything numerous times to get there. I recently talked to him about his path from working as a police officer to becoming a staple in PlayStation’s communications.

Take me back to the first day you thought you might want to work in video games. What was your first experience with games in that capacity?

My best friend from childhood is someone named Herman Richardson. We lived in Mobile, Alabama, and he had a Super Nintendo with Street Fighter II and True Lies. He lived about five miles away. I didn’t necessarily live in the safest neighborhood, but I would walk to his house almost every day after school to play video games. We also played basketball in his front yard. I was horrible at basketball and okay at video games.

How old were you at this time?

We were in middle school, like seventh or eighth grade. Sometimes his mom would drive me back, and I would be like, “Wow, this is really a long walk, because it would take 10 to 15 minutes to drive back home.” It would take me like an hour to walk there. I eventually got a bike, and that made the trek easier. I think that’s where the genesis of my love of gaming came from – those walks and being so excited to play True Lies and Street Fighter II.

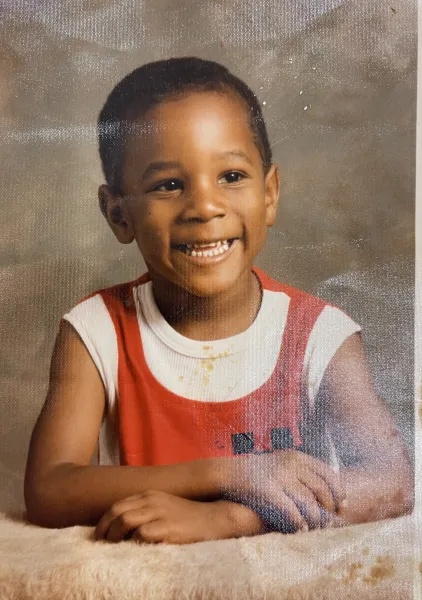

Ramone at age six.

How into games were you? What was your first machine?

Back in 1986, my mother was able to buy me the Nintendo Entertainment System when I was like six or seven years old. She knew someone at a department store, and back then, layaway was a thing. Someone didn’t pick up their Nintendo, and they sold it to her for $99. I didn’t have a lot of games, though. Fast forward four or five years, and the Super Nintendo was released. I never had one of those, which is what led to me walking to my friend’s house to play games on SNES during middle school.

We didn’t have a lot growing up, but somehow my mom made those sacrifices and purchased that first Nintendo for me. I eventually had a Nintendo 64 and the original PlayStation. My love for gaming started around eight or nine years old, but it really exploded after the Nintendo 64 and PlayStation 2 came out.

What was your favorite game back then?

Perfect Dark. When GoldenEye popped, it was the best four-player, split-screen game on any console. We played a ton of that and Madden. And then Perfect Dark came out, and I told everyone, “It’s like GoldenEye, but better!” It’s all we played. The neighborhoods I grew up in weren’t super safe, so we would go outside and play seldomly, but we mostly stayed inside and played games and listened to music.

Some other games that I loved were Super Mario 64, Turok, Resident Evil 2, F-Zero, Blast Corps, Zelda Majora’s Mask, Grand Theft Auto, Tekken, Midnight Club 3, Vagrant Story, just to name a few.

But my dad hated video games and didn’t want me playing a bunch, so I would have to hide my systems. When he went to sleep, I would sneak into the living room, hook up my system, and play quietly. When he saw me playing Ken Griffey Major League Baseball, he eventually started to let us play more. He talked about how Ken was his favorite player, and how wild it was to see him in video game and be able to control him. He talked about his love for sports, and we bonded in that moment. From then on, I could play video games on the living-room TV. But only after homework and only after he finished watching golf or his shows. SOCOM 2 and SOCOM 3 were also game-changers for me. I remember you had to buy that network adaptor to play online, which I couldn’t find for a while. But I eventually did, and spent countless hours playing those games online, doing clan wars until the sun came up. I have so many great memories of SOCOM.

You could die as soon as the match started, because someone threw a grenade across the map into your spawn area.

When you made it to high school and started looking at career prospects, what path did you think you would take?

I was a mess! (laughs) I had no idea what I wanted to do when I was in high school. I didn’t apply myself, but graduated and went to junior college. I flunked out of that. I went to Troy State for one semester. I didn’t take it seriously. When we had to come back to school for the next semester, it was like, “You owe $15,000 to come back to school,” and they brought out all of the student loan paperwork. I was sitting there by myself, and I said, “Let me think about this.” I went back to my dorm and my good friend Walker was getting ready to graduate and had gotten his final bill for student loans. It was like $190,000 or something, I saw that and didn’t know if I wanted to sign myself up for that type of debt. So I went home to try and figure that out.

And did you go back?

When I was home, I saw another friend of mine, who was a police officer at the time. He wanted to know what I was doing, and I told him I wasn’t doing anything. I was trying to make money to pay for college while working at Foot Locker. He was like, “Join the police department. We need more black officers. They’ll pay like 30 to 40 percent of your college tuition.” I thought that was intriguing. I signed up for the police academy, got in shape, and it took me about a year to get in. I graduated and was back in college studying criminal justice and on the Dean’s list, making A’s not that long after. At some point at the tail end of my fifth year of police work, my heart wasn’t in this career anymore. I didn’t want to do it. I didn’t want to do federal, either, since I talked to some FBI and DEA agents. This was after 9/11, so the whole push was on domestic terrorism. I either needed to have a pilot’s license, a computer-science degree, or speak a few languages to get a leg up – those were skills the agencies were looking for at the time and I didn’t have them and didn’t want to obtain them, either. I was like, “I can’t do this.”

In my opinion, there are three jobs you most definitely shouldn’t do if your heart isn’t in it: police officer, firefighter, and teacher. Right? Those are jobs where you have a massive impact on people’s lives, and someone else’s life or well-being could be in your hands. A teacher is dealing with people’s kids. You are responsible for these children during the hours of 8:30 a.m. and 2 p.m. A cop has a gun. It’s a dangerous job and people only call you when something is wrong. You need a lot of integrity, empathy, and compassion. You’re there to serve the community and it’s hard to not take all the pain, suffering, death, and despair home with you. I was in my 20s at the time with no coping mechanisms, and I took it all home every day, and it eventually became unsustainable for my mental health. When my heart fell out of the profession, I knew I needed to go do something else. I was doing soul searching. I didn’t want to do something my heart wasn’t in.

And that’s when you made the jump?

I was like, “Okay, I want to make video games. How the hell do I do that? I’m in Mobile, Alabama.” When Call of Duty: Modern Warfare started to take over, I remember the All Ghillied Up video and how it broke the video game industry since no one had seen anything like that before. Flash forward a few months or a year later, and there was an interview – Mark Grigsby, [Infinity Ward’s] animation director, who is one of my best friends now. I listened and watched him talk about Modern Warfare. I was like, “Wait, there are black people making video games?” I knew there had to be some, but I had never seen one in the flesh and blood or on my computer screen. Seeing him in those videos was the little juice I needed to make me say, “This is something I can do. If he can do it, I am going to be able to do it.” That’s why representation is so important. Seeing someone like me who came from a community like mine gave me the fortitude to step out.

I quit my job as a police officer in Mobile, packed up everything that fit in my car, sold everything that didn’t, and moved to Atlanta. I lived there for three to five years and was homeless for a little while, sleeping in my car. I was working at GameStop for a bit and had no idea what I was doing. I was trying to survive.

But you were thinking of games and that’s where you wanted to be. You were working at a game store.

I knew something would happen if I got to a big city. It wasn’t going to happen in Mobile. Atlanta was the closest city. I had some friends there, too. It was rough. I was broke. Atlanta PD had a program where you didn’t have to go back through the academy if you were already a police officer from somewhere for a certain amount of time, so I could have just taken the physical and possibly joined that department. And I did take the physical, they offered me a position, and the pay was great. But I went back to what I was thinking before I left Mobile; that my heart wasn’t into it. I didn’t move to Atlanta to be right back where I was. I was at the GameStop job; making like $10 or $15 an hour or something like that. In contrast, Atlanta PD, offered me like $50,000 to $75,000 a year. That’s a big difference!

I just loved talking games, though. Having conversations about what was coming out and talking to customers about what they were playing. It made my love of games grow. I stayed at GameStop until I left Atlanta. Back then, there was a website called Madden Nation. I would write crappy articles on the site, and I befriended one of the site’s owners, Will Kinsler, who eventually got a job at EA as a community manager for Madden and NCAA Football. EA had these community days where they would fly people out to playtest games. I was a part of that group after being a part of the Madden Nation community.

Fast forward to me doing that for a year or two, and I’m still in Atlanta. I was a big Xbox 360 guy at that time. It was Christmas Eve, and I was on my 360 and had my headphones on and my laptop up. Will reached out to me randomly for a mic check, and he could hear me typing. He’s like, “What are you doing?” I told him I was filling out my application to go to game design school. He questioned why I would do that, and I told him I wanted to make games, but didn’t know what to do. He told me not to go to school and said I could make games right now with the experience I have.

I was like, “What experience?” He suggested I put everything I had done for EA during those visits on a resume and to send it out. He said that I would get a call in three months or three years. I bulls— you not, three months later, I got an email from two studios. DICE in Stockholm, Sweden, and this now-defunct studio in Reno, Nevada. At this time in my life, I had never traveled and didn’t have a passport, so the Stockholm option was just too scary for me. I ended up taking the job in Reno. I packed up all my stuff, shipped my car to Reno, and they flew me out.

I ended up living with the owner of the studio for a few months because my apartment wasn’t ready. I eventually moved in with one of the programmers at the studio and we became friends. I was with the company for about two or three months, and I got fired.

I’m guessing you began second-guessing your choices at this point.

I sat in my car and bawled because I had just moved across the country. I had no family within five hours of me. What was I going to do in Reno? The programmer let me stay on his couch as long I needed, and told me not to worry about anything. I put my resume back out there and thought I might move back to Mobile. I knew in the back of my mind if I did that, I wouldn’t be in games. I would have done the safe thing, so I had to figure out how to stay in games. I knew I had to get to Los Angeles, California, and I happened to know someone there.

I talked to my friend Greg on Xbox 360 mic chat while playing Gears of War about what was going on, and he told me to come and sleep on his couch until I got back on my feet. I packed up all my stuff again and drove to Los Angeles. It took like 12 or 13 hours, and it was one of the best drives of my life. I was going through the mountains – like an hour into them – and I started smelling pine oil. At first, I thought I spilled something in my car, so I pulled over, got out, and then it hit me, “Oh, this is what fresh air smells like!” I was like, “Holy s—, I’ve never smelled fresh air before!” I realized I hadn’t really been living life. I made the rest of the journey and lived there for maybe four to six months. I don’t remember the exact timeframe. That time was rough. We were eating ramen noodles and Campbell’s soup every day. There was a Big Lots down the street, and I remember we could get a 12-pack of ramen noodles for like one dollar and a big can of this Campbell’s soup for 25 cents. If we made the ramen noodles and put them in the soup, we could eat off that for like two days: breakfast, lunch, and dinner. That’s what we ate most days because I didn’t have a job and my parents had no idea what was going on in my life at that time.

Did you think you would get into games again at that point? You had your resume out there, right?

Yup. I had it out there on all the video game job boards before I drove from Reno. My parents thought I was living it up. They thought my career was taking off, which was not the truth at all. I couldn’t get a job anywhere. I was trying all around town. Since my roommate didn’t have a computer, I had to drive to the library every morning to check my email and apply for jobs. I almost got a job being a tester at Activision. I interviewed for a few other tester jobs. I never got one. Eventually, I got contacted by PlayStation. Shalya Villa, the senior recruiter at PlayStation, contacted me randomly, saying, “Hey, we would love to interview you for this position.”

I thought that was great. I had bad cell service in our apartment, so I had to take the first interview call at the pool. There were people there, and I was on the cell phone walking around the pool trying to stay far away from everyone so Shayla wouldn’t hear all the commotion in the background. Shayla, who is still in recruiting for PlayStation 15 years later, said they wanted me down in San Diego in a week to talk to a few more people. I drove down and interviewed with Jason Villa, production director at San Diego Studio, and Travis Williams, one of my good friends who now works at Meta. I landed the job of community manager, and I’ve been here ever since.

I’m guessing that means you had to pack everything up again and move to San Diego.

I was broke, so I couldn’t afford anything. At this point, I had to tell my parents because I didn’t have the money to move. I called my mom, and she was livid but also happy. My dad, a part of him was proud because I was figuring out my life on my own terms without calling my parents for help, but another part of him was like, “You should have called me if you needed help.”

My mom and my ex-girlfriend at the time, who I am still good friends with 15 years later, found me a place to live and paid for my rent for the first two months. I was living in this little condo in Mira Mesa, about 15 minutes from the studio. It was horrible. I had this roommate who wasn’t the cleanest guy in the world. The walls were originally white, but they were yellow by the time I moved in. There was a mattress in there, and it was the most disgusting one I had seen in my life. I couldn’t sleep on that, so of course, I go to Big Lots, which is again across the street for whatever reason. It’s always there for me. I purchased three cans of disinfectant cleaner, three bed sheets, and cleaning supplies. I cleaned the bathroom and disinfected the whole condo and mattress. I was sitting with two cans of disinfectant spraying the mattress. I don’t know if it did anything. [laughs]

How long did you live under those conditions?

I lived with him for like a year, and then I upgraded to a house with roommates and did that a few times before I had enough money to live on my own.

What was your first game at Sony San Diego?

I was working on all of the studio’s games. At that time, we were making MLB The Show, a basketball game, and a few other titles. The first ones I worked on were MLB The Show and a racing game called ModNation Racers.

What were your first duties?

I was a community manager. For ModNation Racers, I helped set up the beta and create the grief reporting tool for the user-generated content. I also started working on MLB The Show 09 right around the same time.

What I brought to MLB was this concept called “community day” that I learned from EA and Will. I strongly suggested we should have some consumers out to play the game, test it, and tell us what works and doesn’t. When I first pitched it to Chris Cutliff, who is still our studio director, he was like, “Okay, I kinda see what this is.” I asked for a relatively small budget to fly everyone out. I reached out to different communities and brought a bunch of their people out. The development team loved it, and we started doing them every year. We even started doing them twice a year. It changed how we work on and develop our games because we talk directly to the consumers. We find out exactly what they want. We would ask them things like, “What are the top three things they liked in this year’s game and the top three things they didn’t.” You start to see some commonalities in their responses.

That’s how we approached our community. Rather than blanket statements of “What do you want to see,” we focused on those three things or what they liked and disliked the most. We are still doing it to this day.

Could you give us an example of something that popped up and drove development in a different way?

The stadium stuff was a big one. The way that our stadium team works is we have six or seven artists who travel to one to two stadiums a year. Those other stadiums don’t have many reference points [for changes year over year]. We worked with the community saying, “Hey, if anybody has any pictures from last year’s season for the stadium and from these specific areas, send them to us.” Our artist would have a folder filled with reference photos of stadiums that we needed to fix. We would disseminate that information to our stadium artists for the stadiums they couldn’t go visit.

Through the years, you’ve become one of the faces of MLB The Show. You are always there front and center, talking about what’s new in each installment. What’s it like being an ambassador of this series?

That was an accident. (laughs) That all started back at a CES for ModNation Racers. The marketing manager Chuck Lacson, who is also still with PlayStation, needed someone to talk about the game to a camera crew. I think it was IGN. Chuck was like, “Ramone, they are going to turn on the lights and talk to you in like five minutes. Tell them about the game.” He threw me into the fire, and apparently, I wasn’t horrible at it. Leadership thought I should keep doing more of it, and I’m still doing it.

How has your role evolved alongside the annual release of The Show?

I moved completely out of community management maybe five years ago. Could be longer. I just started focusing on other areas. These days, one of my main focuses is being the bridge between marketing, PR, and our development team. I’ll get brain dumps from people on the development team about what makes their work awesome, and I’ll relay that to the other teams. I’ll talk to everyone on the development team over the course of a few months to know exactly what is on the table and why they are proud of it and why it will be awesome. In the last few years, I’ve started to turn it around where I have them talk about their own work [on camera] if they are up to it. It’s their baby. Streaming helped that and allowed people to see what we are working on and hear from the people working on it. I don’t think my role change was anything that was ever written out or defined; it just kind of happened.

Over the years, you’ve been around numerous Major League Baseball players. You must have some amazing stories to tell. Give us one.

There are so many. All the players I have worked with are super nice. We never worked with any athlete that wasn’t professional and nice. I remember some photoshoots back in Florida seven or eight years ago where C.C. Sabathia’s kids were on set, playing the games with him.

In 2017, we put Ken Griffey, Jr. on the cover. This is probably one of my best memories in life. [Sony] sent me out to his house to talk to him to see if it is a fit for us and a fit for him because we had not had a retired player on the cover of the game. I was like, “Okay!” I remember playing Ken Griffey, Jr. Baseball on my Super Nintendo and watching him play on TV. I flew down with my good friend and colleague at the time Jake Jones. We had Ken’s address, and I thought we can’t show up empty-handed. We should bring his wife a bottle of wine and some roses because they are letting these two strangers visit their home. Also, I’m from the South, so that’s just what you do. We went to Target, bought some flowers, and the most expensive Target bottle of wine. We purchased like a $150 bottle, if memory serves correctly. I was like, “Okay, we’re good!”

We’re now driving to his house, and we ran into a wall that ran for like a half mile. We realized it was the wall to Ken’s estate. It was huge. We got to the gate and I had never seen wealth like this in my life. We rang the buzzer, and he wasn’t there yet. He answered from his phone and said he’d be there in like 10 minutes. He was out golfing. We waited outside. He pulled up and let us in. There were 10 cars in the driveway. We got out and walked into his garage. It was bigger than all the homes I’ve lived in combined. His fridge was nicer than anything I had seen in my life.

We met his wife and gave her the flowers and wine. She thanked us, and we started talking to Ken. He apologized for being late. The golf tournament he was at ran long. I believe it was hosted by a winemaker. Ken said since he was sorry, he was going to give us each a case of wine he just got. But we couldn’t fit it in our luggage, he gave us this super expensive and exclusive wine, and we walked in with Target wine. We talked to him, we played the game, and I was like, “This is really happening.”

Ken said he liked us and insisted he treat us to dinner. He took us out, we had a blast, and that’s how [MLB The Show’s] relationship with Ken began. He’s still a friend of mine to this day. It’s surreal.

Building off of that, what does MLB The Show mean to you now?

It’s been a wonderful ride. I’ve gotten to do things I never thought I would. The things that make me happy in life, I’m afforded the ability to do because of this career at PlayStation. I’ve met some truly amazing human beings. I believe the quality of one’s life is determined by the quality of their relationships. And it’s just been fun. Not a lot of downs. We work hard, but it’s been a blast.

And what are you most proud of in your career?

Black representation in the video game industry has been historically low, which is a direct contrast to gaming’s popularity among communities of color. As a company and studio, we tried to identify some ways we could help do our part to change that. Through Sony Interactive Entertainment’s Social Justice Fund, the PlayStation Career Pathways Program was created. Its goal is to support organizations and efforts focused on providing greater educational and career opportunities for historically disadvantaged communities. Our objective is to drive a new era of creativity, development, and growth in the gaming industry.

The first initiative is the Jackie Robinson Foundation MLB The Show Scholars created in partnership with the Jackie Robinson Foundation. The program offers scholarships, mentorships, paid internships, and support to students from underrepresented groups to complete their secondary education and embark on a career path in the fields of technology and gaming.

Uniquely, the Jackie Robinson Foundation provides a comprehensive set of support services to ensure a scholarship recipient’s success in college, in the workplace, and help develop their leadership potential, in addition to the scholarship. Since its inception in 1973 there are over 1,500 alumni and the foundation has maintained a 98 percent graduation rate for its scholarship recipients.

We want to realize the power of education to generate economic wealth for communities of color and have more employees from underrepresented groups within Sony Interactive Entertainment. We are so excited that the JRF was our first partner to help us embark on this journey with us.

For MLB The Show 21, we committed to donating one dollar for every collector’s edition sold to the Jackie Robinson Foundation to build a new scholarship specifically for soon-to-be college freshman students of color who are pursuing degrees and subsequent careers in the video game industry. The Jackie Robinson Foundation is selecting our scholarship recipients right now. As I mentioned briefly, we have paid internships attached to our scholarships. There are five scholarship recipients from the JRF for 2022, and their mentors will all be employees at PlayStation. In their junior and senior years in college, they are going to intern here at San Diego Studio. PlayStation has a marvelous internship program. A decent number of our designers on the MLB The Show development team started as interns.

I think that’s what I’m most proud of. It’s bittersweet, though. I’ve been super lucky and blessed to be in this industry for the past 15 years. Making the games is great, but to be able to help lend a small hand in enacting change, that’s been fantastic. Those first 10 or so years here at PlayStation, I was very much singularly focused. I just wanted to move up that proverbial corporate ladder society tells us is so important, make a few dollars doing it, and help create some great games. I never really took the time to slow down and really take note that I did not interact with very many individuals who look like me from the developer side of things. At E3, or any other conference, there was always a stark contrast to the lack of diversity between who was making the games and the diversity you see from everyone who plays them. I didn’t internalize it. I was just trying to make it. And eventually, I had that thought: If you are in there after you’ve experienced some degree of success, you have a responsibility to open that door for someone else and pay it forward.

Lately, PlayStation has been vigilant in tackling the industry’s lack of diversity. I love working for this company. I hope I retire here. It’s been a great ride for 15 years. Taking this job all those years ago completely changed the trajectory of my life. I’ve been to six of the seven continents, been lucky enough to fill out one passport, and done more stuff than I could ever imagine. All that stems from the opportunities working at PlayStation has provided.

Source: Game Informer The Drive To Make It: Ramone Russell's Journey From Police Work To MLB The Show